I’ve spent a lot of time in 2012 playing games, but not a lot of time writing about them. As I did last year, I’d like to tell some stories or share some thoughts about the ones that meant the most to me this year. I’ll be posting one a day until Christmas. See all Games of 2012 posts.

Moral choices: so common in real life, so frequently deployed as a game mechanic, and so frequently botched in their execution. We’ve come so far in a short time with gaming being able to tell stories and evoke emotions in the player – but forcing a real and meaningful choice seems impossible.

I think it’s caused by the nature of the medium. We are conditioned to stockpile extra lives, to save frequently, to reload our game if we get a bad break. It’s hard to force a meaningful choice – or at the very least, one with permanence – when the world you are making that choice in is so temporary. And so the choices get watered down (Bioshock‘s “Harvest or Save” mechanic) or don’t really matter (Mass Effect 3’s ending) or come so close to the end of the game they don’t cause much divergence at all (the big decision in Grand Theft Auto IV).

So when I started playing Zero Escape: Virtue’s Last Reward, I wasn’t quite ready for what would unfold in front of me. VLR is a visual novel game, a genre relatively popular in Japan but rarely seeing the light of day in the US. It’s the sequel to the very well regarded 999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors, which I hadn’t played but had been told was excellent.

Some spoilers are going to follow because part of what I love about the game is intrinsic to the plot:

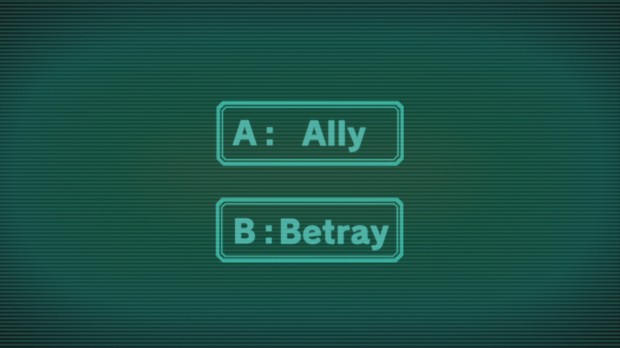

The game focuses on the running of “the nonary game”, somewhat reminiscent of what you might see in a knockoff of the Saw movies. 9 people are trapped in a strange facility; they are forced to explore it in groups (which are basically a series of Escape The Room puzzles). On occasion, the teams get sent into isolation rooms to vote whether to trust or screw over their partner(s)[1. If this sounds a lot like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, rest assured the game is not trying to hide that. In fact, it provides you a full logical dissertation on how it works and all the strategies that one might implement.]. Points are gained and lost based on those votes; anyone who reaches 9 points can leave the facility, but once the door out closes, it will never open again. And if your points hit 0? That friendly bracelet injects you with drugs and you die.

From the get go, VLR makes what seems like some odd design decisions. It puts the story tree front and center on the menu screen, telegraphing when the choices that matter (largely those votes) are approaching. You can jump around the story tree whenever you see fit. So it seemed straightforward for me to grind through it: play to the bottom of one decision tree, jump myself back to the last decision point, go the other way, and gradually see all the endings.

I barreled down the right-hand side of the tree in a couple of hours, but something odd happened. I neared the bottom, but the game hit a cliffhanger and I was sent back to the tree. Confused why I couldn’t proceed, I went to the previous choice and went the other way – and got completely mind-fucked when a character was confused why I hadn’t made the other choice. The one I had made minutes prior. (And that still didn’t help me get past the roadblock.)

Virtue’s Last Reward is a brilliant game because the temporary nature of your choices is not merely a gameplay mechanic, but also integral to the plot. The game doesn’t just allow you to you skip around the story tree, it demands it if you’re going to see the complete ending. You will repeat events under multiple circumstances, and the information from one distant timeline may help you get past challenges in another. (Of course, your ability to know about things that haven’t happened becomes concerning to the other characters, who all have their own motivations and backstories.)

Working up and down the story tree is time consuming, although a brilliant “skip dialog I’ve already heard” button saved me from deja vu. But I started from a state of knowing nothing, absorbed the world across multiple timelines, and then suddenly understood why I needed to understand all those timelines. Kotaro Uchikoshi’s script twists and turns in ways I’ve never seen a game manage before.

The biggest compliment I can give Virtue’s Last Reward: its unique storytelling and construction hooked me so hard, I ended up with a platinum trophy on PSN for it. (And I can’t wait for the next game.)

Virtue’s Last Reward is available for the 3DS and Vita. My experiences were with the Vita version.